Attendees pose at a conference at the University of Regensburg titled "Behind the Veil: Analyzing the Hidden Patterns of Spiritual and Sexual Abuse among Catholic Women Religious." (Courtesy of Lucy Huh)

Editor's note: This story is part of Out of the Shadows: Confronting Violence Against Women, a series by Global Sisters Report and Global Sisters Report en español, focusing on how Catholic sisters respond to or are affected by this global phenomenon.

(GSR logo/Olivia Bardo)

This summer, the subject of various types of abuse of Catholic sisters rose to importance, with two conferences focusing on the issue.

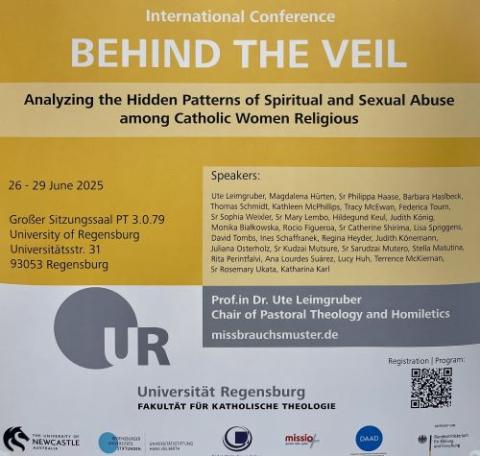

One conference, held in Rome, was sponsored by a collaboration of the U.S.-based Conrad H. Hilton Foundation (a major funder of Global Sisters Report) and the German Missio Foundation. One in Germany was sponsored by the University of Regensburg and titled "Behind the Veil: Analyzing the Hidden Patterns of Spiritual and Sexual Abuse among Catholic Women Religious."

Lucy Huh, a doctoral candidate and researcher at Baylor University, was invited to participate in the June 26-29 Regensburg conference, as she is currently conducting a study of about 100 victims abused by clergy in adulthood.

"Besides being a basis for more research, most important is that this conference succeeded in taking an honest look at what is 'behind the veil,' " Huh said. "It created space for honest and open discussion within academic and church contexts. The goal was never to attack religious life but rather to help make it safer and more authentic for all involved."

Recalling her experience at the conference and the many panels that untangled the subject's complexities, Huh spoke with Global Sisters Report about sisters as both victims and perpetrators of abuse, and the power dynamics at play.

GSR: What was your particular interest in this topic?

Huh: My particular interest in this topic stems from my own experience having spent time in religious life, which gave me firsthand insight into the dynamics and vulnerabilities that exist within these communities.

Lucy Huh, a doctoral candidate and researcher studying victims abused by clergy in adulthood, participated in a recent conference in Germany on the subject of abuse. (Courtesy of Lucy Huh)

You mentioned to me that this academic conference was groundbreaking. Can you say more about this?

Although gendered violence in religious communities has been identified as a global problem through multiple public inquiries over the past 20 years, specific experiences have been largely ignored. They wanted to move the conversation from "epistemic injustice" — the systematic exclusion of certain voices and experiences — to "epistemic awareness" that takes seriously the experiences and insights of those affected by abuse. This means moving beyond denial or minimization to honest examination of systemic factors that enable abuse, and then how authority and community structures can be reformed to prevent abuse and survivors can be supported rather than blamed.

Another [reason this is groundbreaking is] that Dr. Ute Leimgruber [professor of pastoral theology and homiletics at the University of Regensburg and the conference organizer] and a team of organizers recognized that the silence about significant levels of sexual and spiritual abuse needed to be addressed, not only about sisters as victims, but also as perpetrators.

These sound like very interesting goals, especially the epistemic injustice to epistemic awareness, words I was not familiar with. Also, we have not heard much about sisters as perpetrators.

I understand that the program featured a number of panels. What were some of the topics?

Yes, there were six panels, each addressing different aspects of this complex issue. The first one was called "Speaking, Listening, Believing." Speakers spoke about the importance of lifting the silence so that the issue can be made public. Journalists help this, but more important, the individual voices of the women need hearing, disclosure and then believing.

A flyer for the conference "Behind the Veil: Analyzing the Hidden Patterns of Spiritual and Sexual Abuse among Catholic Women Religious" (Courtesy of Lucy Huh)

[For example, the Rupnik] case was analyzed by Federica Tourn, the Italian investigative journalist who broke the story, to show the way silence of abuse is maintained because [Jesuit Fr. Marko] Rupnik was a famous artist. Victims felt no one would believe them if they spoke up because of who he was, a priest and artist. Finally, she investigated and surfaced the case publicly. I witnessed the impact of this when I visited Lourdes and saw that his art, which covered the basilica, was no longer being illuminated at night, and finally ended up being covered. It took a long time.

Yes, it seems that is the pattern of how these things go on and on without anyone speaking up. So, what followed this panel?

The second panel on sexual abuse of sisters presented studies of sisters in Africa and Germany abused in their communities. It identified sisters both as victims and perpetrators, both happening because of an underlying power dimension that enabled abuse to take place. When victimized by priests, disbelief is often registered by superiors, usually judging the sister and often not believing it was nonconsensual. When judged this way, sisters are left to bear the guilt and pain in silence. It can even be harder to be heard when the abuse happens with community members and even superiors within the religious community.

Advertisement

During the conference, there was emphasis on a concept related to vulnerability that many have not heard before — "vulnerance."It was described as a susceptibility to being harmed due to the factors that exist in the environment itself, such as a pastoral counseling relationship. Researchers examined how systemic factors within religious communities themselves create conditions for abuse to take place.

Things like, prioritizing secrecy or self-preservation over the well-being of members; or exercising spiritual authority, "obedience," "God's will," to manipulate and weaponize power in order to maintain control over others. To counteract these systemic factors, a framework around vulnerability, "vulnerance" and resilience was proposed. It called for examination of community systems and practices that might be creating vulnerability of members and weakening their capacity for resilience for recovery. Later on, the fourth panel presented how this framework of vulnerability, "vulnerance" and resilience could work in communities.

This is really powerful and important for congregations to look into. So, please go on.

The third panel addressed the negative and positive aspects of how faith beliefs, theological traditions and gender impact abuse situations. One speaker spoke about how "God's will" can be used by perpetrators as a tool for manipulation and even a kind of enslavement whether for spiritual or sexual abuse. Another speaker spoke about the importance of spirituality for resilience. She used an example from the Kuibuka program used in Rwanda after the genocide or other programs that help survivors grieve, but also empower persons spiritually to become agents of change in communities.

Just listening to all you learned is an education for me. I'm eager to hear about the focus of the fifth panel.

It was also really informative. The fifth panel was called the "World Café," and I found it particularly innovative. Representatives from all continents spoke to issues of abuse among women religious specific to their regions of the world. As we listened, it was clear that the issues were not isolated to particular regions or cultures, but instead reflected patterns transcending geographic boundaries, manifesting in culturally specific ways. Something that stood out for me too was the issue of colonialism, which I came to understand has been a kind of blind spot in previous discussions. There are definite colonial legacies that influenced power structures in religious communities.

My part in this session was with a partner, Terence McKiernan, co-founder of BishopAccountability.org. He has been instrumental in documenting and tracking abuse in the Catholic Church through digital archives that preserve testimonies that would otherwise disappear. We presented the situation in North America. We formed a timeline from the 1950s and noted key moments in American history regarding abuse of and by women religious. We also mentioned pivotal moments and figures who shaped these issues.

Could you share who some of the figures were from North America?

We shared about how sisters have uniquely shaped American history as they ran schools, hospitals, orphanages and other institutions. We highlighted survivors like Sr. Jane McDonald, who was abused by Sr. Jeanne Wilfort of the Sisters of the Holy Cross in Manitoba under the guise of healing childhood trauma. We also highlighted other cases like the Ursuline Sisters case in Montana, which resulted in a 2015 settlement of $4.45 million to 232 plaintiffs and involved both priests and sisters as perpetrators. Additionally, we featured institutional advocates like Phil Fontaine, who brought crucial attention to abuse in residential schools in Canada, and women like Mary Dispenza, a former nun who was abused in the convent and later left to become an advocate for those who have suffered abuse by nuns and sisters, forming the first nun abuse support group through SNAP. We also discussed Doris Reisinger, who has served a pivotal role bridging the gap between Europe and North America in shedding light on the issue of abuse of sisters.

What a rich experience to be both listener and presenter. I can see how this conference has provided a lot of groundwork for future research.

Definitely. Although much attention has been given to clerical abuse, the conference opened new conversations through presentation of academic studies about abuse within women's communities. Members were recognized as both victims and perpetrators, rising out of unique factors like gender dynamics, nature of religious life and particular vulnerabilities within communal living and spiritual authority structures. So, a lot more research is needed. What is exciting is that a global survey on Catholic women religious is being planned to provide broader data.

Being part of this conference was deeply meaningful to me, and I look forward to contributing to the crucial research that must follow. This gathering has opened doors for the kind of transparent examination and healing that these communities and the Catholic Church at large desperately needs.