St. Joseph Sr. Pat Bergen speaks at the January 2016 news conference announcing the plans to convert the congregation's former provincial house in New Orleans into a water garden. Listening are Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, second from left, and then-mayor Mitch Landrieu, third from left. (Courtesy of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph)

Editor's note: It's the five-year anniversary of "Laudato Si', on Care of Our Common Home," Pope Francis' landmark encyclical on the environment. Read about other things sisters are doing for the environment on GSR and follow NCR's Laudato Si' anniversary coverage on EarthBeat here.

On a beautiful June day in 2006, St. Joseph Sr. Joan Laplace was driving back to New Orleans after visiting the Gulf Coast with some sisters when her phone rang.

It was from a sister in Cincinnati, asking how far Laplace was from Mirabeau, the New Orleans provincial house of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph.

"There's been a fire," the sister on the phone said. "How soon can you get there?"

Laplace arrived to find the campus filled with firefighters and equipment. A helicopter ferried loads of water from the nearby Bayou St. John.

"It was an absolutely beautiful Sunday afternoon," Laplace said. "It was a ridiculously fine day. But there was apparently a tiny little storm, and lighting had struck the roof of the center building and traveled in every direction."

By the time the fire was out, the second floor of the building no longer existed.

The first floor offered nothing to save. It had been gutted months before after 8 feet of water flooded it during Hurricane Katrina in August 2005.

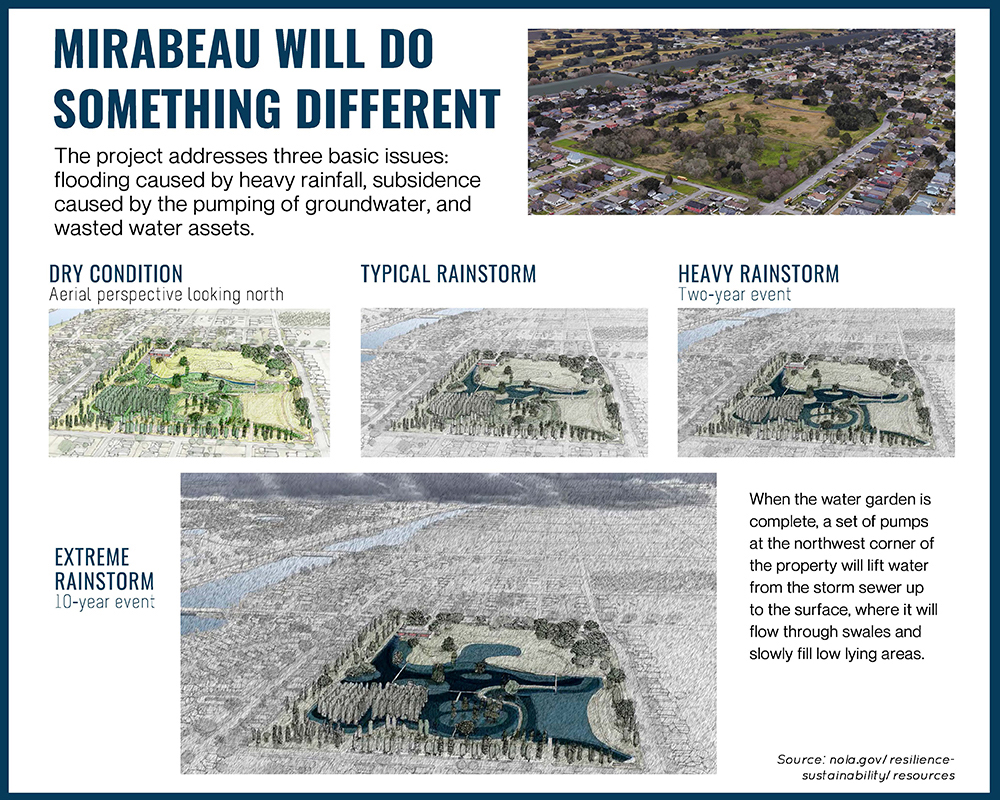

Soon, it could be flooded again, but this time, the water will spare local homes and businesses; feed 25 acres of prairie, wetlands and forest; and help stop New Orleans from sinking further below sea level. The sisters hope for an August groundbreaking to transform the land into a massive water garden, a place to store floodwater during storms.

"New Orleans has never managed water," Laplace said. "They've always fought it. This is water management."

There is a large storm sewer running beneath the street on the north edge of the property. In normal times, that system drains rainwater from the streets of the neighborhood to Bayou St. John. But the bayou can only hold so much water, so the storm sewers fill up and rainwater floods streets, then homes and businesses.

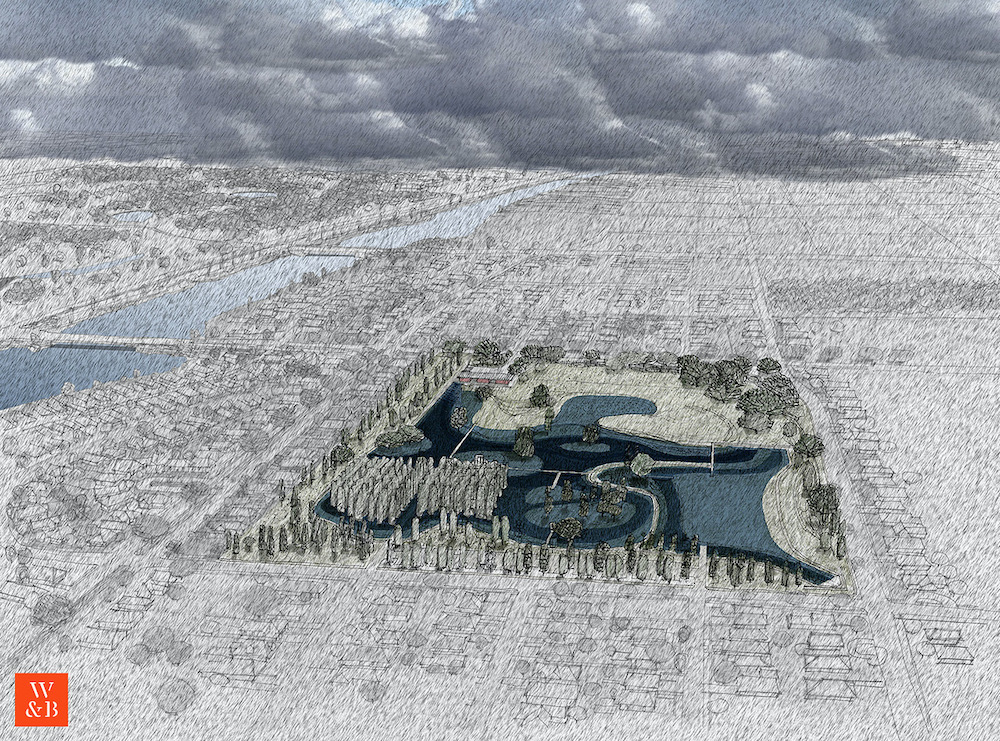

Illustration of the planned Mirabeau Water Garden in New Orleans showing a 10-year flood scenario (CNS/Courtesy of Waggonner & Ball)

When the water garden is complete, a set of pumps at the northwest corner of the property will lift water from the storm sewer up to the surface, where it will flow through swales and slowly fill low-lying areas.

Another storm sewer at the southeast corner of the land will drain onto the land by gravity. A small berm around the edges of the property will ensure the water stays where it belongs as it waters the landscape, soaks into the soil and evaporates. When the storm sewers have capacity again, the water — up to 10 million gallons of it — will flow out of Mirabeau back into the city system and to the bayou.

Architect J. David Waggonner III, who proposed and designed the water garden, said one of the biggest problems facing New Orleans is the way it has fought the water.

Yes, the city does lie below sea level, but it didn't always. A century of pumping water out of the ground to lower the water table has caused the land to sink — a process called subsidence — up to 8 feet in places, he said. That means the more engineers use pumps against the water, the deeper the hole they find themselves in.

Mirabeau will do something different.

Instead of pumping out groundwater and causing more subsidence, Waggonner said, Mirabeau will return groundwater — and more than engineers originally thought. In studying the land, they found what was once a barrier island thousands of years ago that is now underground, meaning a huge tube of sand is there that can easily move groundwater away, making room for more.

"This is not designed to protect you from storm surge. It's designed to protect you from rainfall, which is a much more common occurrence," Waggonner said.

St. Joseph Sr. Pat Bergen, right, with architect J. David Waggonner III (Courtesy of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph)

When complete, the Mirabeau Water Garden — land the sisters still consider holy, a place where generations of sisters lived and worked and served God — will serve the neighbors, their city and the environment and will be a model for other cities dealing with stormwater.

Today, the 25 acres of Mirabeau is empty save for the horseshoe-shaped driveway that led to the main entrance and a large piece of concrete bearing the congregation's shield that once marked the center of the lobby floor.

Massive spreading oaks form a grove near the northeast corner of the land. The center of the property is mostly prairie, and the southern end is lightly wooded.

The process hasn't been easy. Waggonner met the sisters in 2008, but it took years to come up with preliminary designs and apply for and receive federal funding. They had to deal with the local bureaucracy, state government and multiple federal agencies; those processes took time. Once the funding was in hand, the plans were announced in January 2016. Since then, Waggonner's firm created has construction plans and gone through the permitting process.

Now, it is ready to be bid on, and work could start within months, depending on the status of the COVID-19 pandemic. After more than a decade of planning, the sisters, now based in Baton Rouge, are long past mourning the loss of their old home.

"I'm praying not for an end" to the process, Laplace said, "but an end to getting it started."

Mirabeau was where Laplace's consecrated life began.

She was 18 years old and knew the St. Joseph sisters well. Her family lived in New Orleans, and she had gone to their high school in the Tremé neighborhood. On Sept. 8, 1960, Laplace entered the order, and Mirabeau became her home for the next few years.

At that time, Mirabeau was a busy place, with about 125 sisters living there. For the first nine months, Laplace and her fellow postulants lived together in a dorm: 16 women in a single room with beds separated by white curtains.

"I would call [the building] functional. It wasn't built for the beauty of the architecture," Laplace said. "But the grounds were beautiful."

(GSR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

A providential meeting

In 2008, a mutual friend introduced Waggonner to a woman considering joining the Congregation of St. Joseph. Waggonner at the time was hosting a series of workshops he called the "Dutch Dialogues," examining how the Netherlands managed water rather than simply trying to fight it by building ever-bigger infrastructure.

Soon, the sisters and Waggonner met under the spreading oaks at Mirabeau, but the sisters were skeptical, said Sr. Pat Bergen, who was on the leadership team at the time.

Developers were already approaching them, salivating over 25 acres of open land in the heart of the city, but the sisters were not about to have Mirabeau turned into a sea of chain restaurants and strip malls.

Waggonner was different.

"Everybody's got a plan," Bergen said. "We said, 'We only have a half-hour, so make sure he's on time.' Of course, we would have given him hours and hours once he started talking."

It was more than just his philosophy of managing water.

"He has this sense, like many artists do, of the spirituality of the land, and that resonates with us," Bergen said. "We really believe this land is holy. People have prayed there for years and years and years. And this land could bless the water as it held it before it returns to the canals."

Waggonner grew up in the woods of north Louisiana in a faith-filled Protestant family. In the early 1990s, he met Dominican Sr. Ambrose Reggio. He was working on a high school for the congregation, and Reggio was in charge of the campus, so they worked closely together for several months.

"She was one of the most influential figures in my life," Waggonner said. "The construction meetings would start with a prayer. It was the best construction job you could have. The atmosphere was just totally different. So I have a deep bond and a love for the sisters."

Now, Waggonner has designed a new future for Mirabeau, one where it becomes the flagship of the Gentilly Resilience District, a plan to turn a large swath of New Orleans into an area that manages its stormwater through diversions, storage and infiltration instead of more pumps and higher levees.

"That's why this project is so important," he said. "It goes beyond the 25 acres. This is where the sisters have this intuition: There's something the Earth does for us, there's something grasses do for us, there's something trees do for us."

Others agree: The first phase of the project is funded by a grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the second will be part of a $143 million grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to the city.

St. Joseph Sr. Joan LaPlace (center, in black) with St. Joseph sisters in the library of St. Joseph's Academy in Baton Rouge, one of the Catholic high schools the order founded (Courtesy of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph)

'We were so happy'

Today, the sisters are preparing to lease the land to the city for 99 years for $1 a year, Bergen said, and they hope groundbreaking will occur soon. They don't know how far the pandemic will push things back.

"All the money is there. It's just not being used," she said.

The sisters know they could have simply sold the land for millions of dollars, but that would have hurt the neighborhood environmentally instead of helping it.

"The thought did come up that we could use that money for something good, but the people of the neighborhood would be in the same situation," Bergen said.

Instead, they helped get grants, including a massive federal grant, to pay for their project.

"We didn't get anything out of it," Bergen said, laughing. "We were so happy."

Waggonner said the choice of protecting the land versus pocketing the money was an easy one for the sisters.

"They didn't agonize over that," he said. "They have a higher agenda."

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook.]

Advertisement