Staff, volunteers and family members of farm director David Hambleton work July 4 to harvest 10,000 garlic bulbs — the supply for this year's CSA members and seed for next year's crop. (Courtesy of Sister Hills Farm)

Editor's note: The phrase "just transition" is part of the growing lexicon about moving from an economy based on fossil fuels to clean energy. But this phrase's meaning varies. The term can also mean the need for a just transition to new jobs for those employed in industries such as mining. Catholic sisters are involved along the spectrum of transition efforts.

With November and the Thanksgiving season comes frost, a nip in the air and time to reflect on the recent growing and harvest seasons.

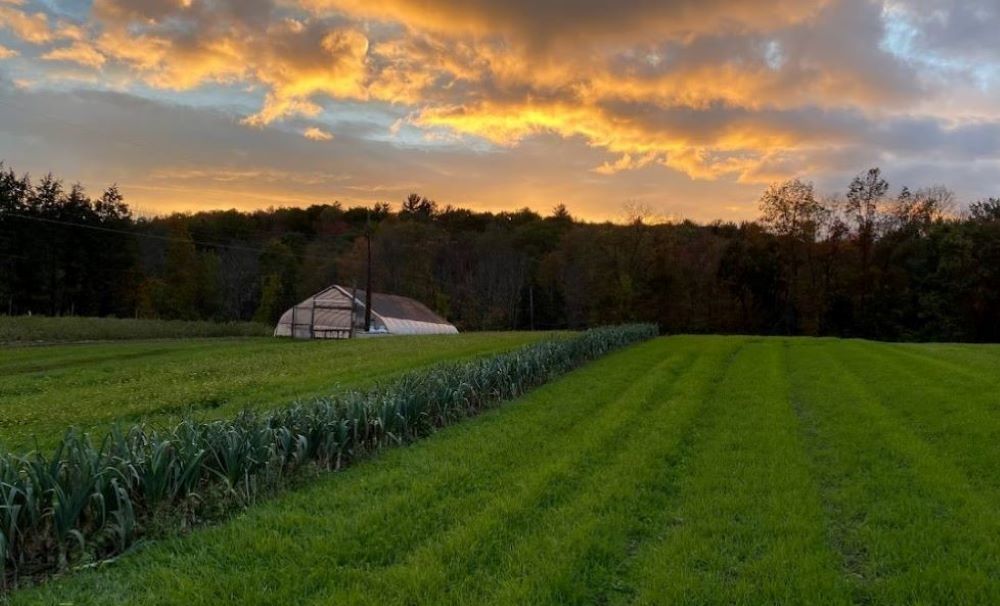

For farmers David Hambleton and Ella Schwarzbaum it has been a good year at Sisters Hill Farm, despite a hot, humid summer and a wet, rainy autumn.

Every cycle has its challenges, they say, though what unites and binds the years and seasons together is the rhythm of the land, the belief that their work is doing good for a just transition to a more sustainable planet, and that their labors are spiritually grounded.

"This is definitely a call," Hambleton said, reflecting on his experiences as farmer, since 1999, and director, since 2017, of Sisters Hill, a 10-acre farm near Stanfordville, New York. A ministry of the Sisters of Charity of New York, Sisters Hill is one of several farms in the U.S. that have put sisters’ environmental ethics and commitment to practice.

"It encompasses so much. It's just not growing the food,” Sr. Mary Ann Garisto, who was director of the farm 1997 to 2017 and now holds the title of farm director emeritus.

Garisto remains one of the farm's biggest boosters. "It’s a spiritual thing," she said. "It’s a mutual relationship. It's friendship. It's people getting together. It's caring for the earth. It's just so much more than vegetables."

Sisters Hill, like other farms with congregational ties in New York’s Hudson River Valley, including Harmony Farm in Goshen, is a community supported agriculture (CSA) farm. That means it is not for profit and provides produce to members and to nonprofits and charities, such as food banks.

Like other farms, the amount of land used for farming itself is only part of the property; the sisters originally owned 141 acres, but half of that has been turned over to a local conservation group as a land easement, Hambleton said.

A sign on the road leads to Sisters Hill Farm in Stanfordville, New York, a ministry of the Sisters of Charity of New York. The farm is named after the road. (Chris Herlinger)

There is not a definitive number of CSAs in the United States and the U.S. Department of Agriculture listing of CSAs — nearly 1,000 — is far from precise or complete, said Kirstin Bailey, a senior project associate for the Nebraska-based Center for Rural Affairs, a national advocacy group.

There may be a few dozen such farms associated with women’s religious congregations in the country, said Sr. Miriam MacGillis of the Dominican Sisters of Caldwell, New Jersey, co-founder of Genesis Farm in Blairstown, New Jersey, which is considered a pioneering model for such farms. She counts at least 32 farms, gardens or ecological centers alone that have roots in educational seminars held at Genesis.

(A number of congregations, such as the Dominican Sisters of Hope, also in the Hudson River Valley, do not have farms, but maintain gardens that provide vegetables for their residents and for local charities, such as food pantries and food banks.)

CSAs, Bailey told GSR, are models of sustainable agricultural practice.

"CSAs are a great way for local farmers to connect with their customers directly," Bailey said in an email. "They are able to provide seasonal, fresh produce from their farm to consumers at a fair price without having to go through someone. This system chips away at the corporate food structure predominant in the U.S. by returning to quality products that are priced high enough for a farm to survive."

In paying for membership, CSA members are "fronting" the money for farmers "to purchase seeds, upgrade or install infrastructure, and have income prior to the growing season," she said.

Sisters Hill estimates that in the last 22 years, it has "grown and shared" more than 1 million pounds of produce with its members and charities.

To Hambleton, 48, a native of Orange County, New York, and who heads a crew of four — two farmers and two apprentices — this represents a needed service. But it is also an alternative to the corporate model of farming in which food is produced on a large scale and distributed nationally — for profit by multinationals that generally do not have ties to local communities and are rarely concerned with "earth-friendly" sustainability.

Advertisement

The CSA model offers a possible pathway to a just transition toward a more eco-friendly approach to producing and sharing food. "The way I try to farm is to promote a well-balanced ecosystem," Hambleton said as he and Schwarzbaum finished working on a bright, cool November afternoon.

In mono-agriculture, the model for large corporate farms, single crops are grown for maximum yield — and maximum profit.

But what that does is "mine the soil," wearing the soil's resilience. "That's not a naturally healthy environment," Hambleton said, noting that the use of pesticides at such farms actually boosts the resilience of insects against pesticides and increases the possibility of plant disease.

The emphasis at Sisters Hill Farm and the other sister farms is a "balance —a naturally healthy environment, a natural functioning resilient ecosystem" in which pesticides are not used, and different crops are grown side by side, Hambleton said.

"We are a model for a better connection to the earth and to our neighbors," he said.

Sisters Hill Farm, shown at sunset in October 2021, is a ministry of the Sisters of Charity of New York in Stanfordville, New York. (Courtesy of Sisters Hill Farm)

On Tuesdays and Saturdays during growing and harvest seasons, those neighbors are members in the immediate area who come to pick up their share of produce in this quiet, peaceful ecosystem of rolling hills, valleys and flatland, streams and tributaries, not far from Poughkeepsie, New York.

Also on Tuesdays, the neighbors include CSA members in New York City, about 100 miles south of the farm. Of the 380 families receiving "shares," about 60 live in the city. Members receive 4 to 20 pounds of food a week — usually including lettuce or loose greens and seasonal vegetables. Distribution is for 24 weeks — roughly half a calendar year — May to November.

In late October, city CSA members stopped at the campus of the College of Mount St. Vincent, a liberal arts institution founded by the Sisters of Charity and located in the leafy, residential area of Riverdale in the New York City borough of the Bronx.

There, Hambleton greeted members and friends — as did Garisto, who at age 89 says she has been blessed with energy, vigor and a continued passion for Sisters Hill Farm and its mission.

Standing next to containers of fresh vegetables — potatoes, winter squash, garlic, onions, green tomatoes, arugula, Swiss chard and lettuce — Garisto praised Hambleton, who was raised Lutheran, for his "deep spiritual values" and longtime commitment to the farm. "I call him a Renaissance man because he can do anything," Garisto said. "He’s been with us from the beginning and he's in sync with the mission of the Sisters of Charity."

Several factors played into the creation of the farm, and her 20-year leadership, Garisto explained.

One inspiration was a New York City neighbor— the late renowned theologian Thomas Berry, a Passionist priest and founder of the Riverdale Center of Religious Research. Berry's 1990s lectures focused on the intersection of theology and ecological concerns and his personal engagement with the Sisters of Charity awoke Garisto and other sisters to the burgeoning field of ecotheology.

"Berry did so much for this whole movement, of bringing people to understand that we are all interconnected," Garisto said. "That we're all part of this earth. We're all in it together."

Another element of awakening was a 1991 sabbatical Garisto took at Genesis Farm and meeting MacGillis. Garisto credits the Dominican sister for being an "inspiration and mentor" and introducing her to the idea of community-supported agriculture.

Luckily, her congregation had the land on which dreams could be created.

"A light bulb went off in my head. I said, 'Wow. We have this property at Stanfordville. It was a farm. There's a history to it.' "

The congregation had owned the land since 1916, when it was donated by a couple who appreciated "what the sisters had done in New York City ministries and wanted a place for them to be able to just go and relax."

The sisters had run a farm there until World War II, when there weren't enough men to do the physical farming. Eventually, Garisto said, the farm fields were left open, and neighboring farmers used them to grow hay.

With available land, Garisto — inspired by Berry and the example of Genesis Farm — was determined to make the site a working farm.

The congregation's initial reaction was not positive because environmental concerns were not yet a congregational priority. That would eventually change, however, when the sisters embraced "care for the earth" at its 1995 chapter meeting.

"The time was ripe," Garisto recalled. Congregational leadership began "waking up and realizing that, 'We're living in a different world right now.' " With the available land, the congregation decided that, "Yes, we need to do something."

After years of study, contemplation and persistent advocacy by Garisto and others, Sisters Hill Farm opened in 1997 – the name taken from the road where the farm sits.

"There were a group of dedicated sisters who worked with me when we started the farm," Garisto said, adding that Sisters of Earth, the informal network of U.S. and Canadian sisters, reinforced the ecological-based work of her congregation.

And while proud of the practical results from the farm — providing produce in an environmentally sound manner — Garisto is equally proud that that the congregation's values are being lived out.

"Sisters of Charity have always been advocates for people who are poor, for more than 200 years. If we were going to do this farm, there had to be some component, some way in which we would be able to connect with people who are poor," she said.

From the beginning, the sisters decided to donate about 10% of the harvest each week to soup kitchens and food pantries. The donations go to organizations, both in New York City and in the immediate area. The farm also provides free shares, or subsidized shares, to those needing food. "We don't turn anyone away," she said.

Though the harvest season is at its end, a Thanksgiving "bonus" distribution day is an annual event — giving out "squashes and stuff like that," she said.

"I tell people: 'This is your farm. It's our farm. Just come any time. Sit down.’ It's a wonderful place of peace and serenity."

Connecting to the land

A similar spirit and feeling of quiet and serenity envelops Harmony Farm, a 285-acre stretch of land in Goshen, New York overseen by the Sisters of Saint Dominic of Blauvelt, New York.

Like Sisters Hill, Harmony Farm runs a CSA program — now at 30 families — with produce coming from a 7-acre plot; the property also includes a retreat house that was formerly a boarding school. And like Sisters Hill, the land has been a sisters-owned property for decades, with the working farm beginning in the 1990s. The congregation is discussing putting some of the property into a land trust.

In late October, just as the harvest season was ending, several sisters and volunteers were preparing for the season's final shares, and for a food distribution the next weekend at the First Presbyterian Church in Goshen.

In the kitchen, Blauvelt Srs. Ellenrita Purcaro, 74, the farm's co-manager, and Gertrude Simpson, 87, a volunteer, were preparing a lunch of pasta and fresh vegetables; the aroma of just-peeled garlic wafted through the air.

For Simpson, a longtime religion teacher at St. Raymond Academy in the Bronx, time spent at the farm is spiritually renewing but also rekindles a personal connection; she spent time there as a high school student during summers. "It's part of my roots," she said.

The farm's caretaker, Chris de Goede, 67, has lived on the site for 37 years. He does all manner of work — from building maintenance to assisting with farm work itself — and praises the sisters' leadership and property management. "They listen," he said of the sisters. "No one could be as wonderful to work for."

Over lunch, Purcaro mused about the importance of fresh, locally grown food. She said the farm's CSA program allows people to feel a bit connected to the land — a needed corrective in a society where mass-produced food harms both land and bodies.

"We don't know what we're eating," she said of the overall food system. "Everyone should have some idea of where your food comes from." In a later email, she elaborated: "Many of us are so disconnected from our natural resources we are not attentive to where our food or water comes from, where they are flourishing or where they are in danger. We need to ask the questions, buy local, check our wells and water sources."

Sr. Didi Madden, a Harmony Farm co-manager, says that farms like Harmony are making small inroads against a corporate-run food system that is probably not sustainable in the long run. "Why is there a problem?" she said of mass-scale farming. "We look at land as a commodity. (Chris Herlinger)

After lunch, in one of the fields, Sr. Didi Madden, 64, another farm co-manager, continued that discussion, saying that farms like Harmony are making small inroads against a corporate-run food system that is probably not sustainable in the long run.

"Why is there a problem?" she said. A key issue is that mass-scale farming looks at land as a commodity, used to feed "into a system of constant want," she said.

"I think a culture of comfort is killing us," she said. "People go days without eating 'real food.' "

Such food was very much in evidence as the sisters’ eggplant, peppers and garlic were among the items distributed at a parking lot of the First Presbyterian Church in Goshen under the auspices of the Goshen Ecumenical Food Pantry.

Purcaro dropped off produce early the morning of the distribution. Volunteers placed the vegetables into bags, along with other donated food items, to clients who, in a COVID precaution, drove up in their cars.

Longtime volunteer Carolyn Keller participates at a Saturday morning food distribution, which includes vegetables from Harmony Farm, at the First Presbyterian Church in Goshen, New York (Chris Herlinger)

Carolyn Keller, a church member and a longtime food pantry volunteer, said people appreciate the sisters' fresh vegetables. "Fresh is best," she said.

The line of cars came to 33 that day, with an estimated 61 families served — double the 31 families receiving food at a previous distribution earlier in October. Longtime volunteer John Strobl said such a jump is not unusual close to the end-of-the-year holidays.

He and volunteer Susan Armistead praised the sisters for their contributions to an effort that represents the work of a half dozen faith traditions.

“The sisters are wonderful,” Armistead said. “What they’re doing is sharing the fruit of their labors.”

Tangible and spiritual rewards

The labor is constant – even on modest-size farms like Sisters Hill there is always work to do, even as the harvest season ends. The hours tending vegetables are long. But the rewards are immense, the farmers say, partly because they are tangible.

"There are a lot of people doing good work, but you don't always see the good you're doing," said Schwarzbaum, 28, who grew up on New York City’s Upper West Side and majored in environmental studies in college, as Hambleton did.

"There’s something good about tangible work," she said. Schwarzbaum was an elementary school science teacher and became the farm's assistant manager in 2020 after her initial apprenticeship. "It’s good to talk to people who eat our food."

Perhaps less immediately tangible but still very real in the experiences of the farmers are the spiritual examples of the Sisters of Charity they have known through the years. “I always have the sisters in my head,” Schwarzbaum said.

Sisters Hill Farm Director David Hambleton, right, and Farm Director Emeritus Sr. Mary Ann Garisto prepare a member's produce share to be picked up at the distribution at the College of Mount Vincent in the New York City borough of the Bronx. (Chris Herlinger)

Hambleton agrees. Yet he is also aware of the concerns Garisto and others share: for now, the model of Sisters Hill Farm cannot be suddenly replicated immediately – the corporate food model is not going to be altered overnight.

"I know I can't solve all of the world's problems," Hambleton said sitting on a porch as the slant of autumnal light started to dim in mid-afternoon. "But I can have an impact on my family, my neighbors, the sisters, where I live," he said. "It's an expanding circle, a ripple in the pond."

It's important to keep those ripples in mind but to keep sight of the larger challenges, Garisto said. "You can't do it without having systemic change," she said, and that road will not be easy. Never underestimate corporate power or intransigence, Garisto warns.

"These corporations have to change, but they're not going to, because they're only interested in money," she said.

But the farming model she others advocate is at least a beginning – the seed of a just transition to a more sustainable planet.

Said Garisto: "It’s about all of us working together."