Sr. JoAnn Persch, a Sister of Mercy, addresses a rally to protest detention and to remember those children who died at the border. Sponsored by the Chicago Archdiocesan Office of Immigration, the rally was held in 2019 at Holy Family Parish peace garden in Chicago. (Courtesy of JoAnn Persch)

Editor's note: This is Part 2 of the "At America's Door" series. Read Part 1 here: "How nuns, once suspect, won the heart of non-Catholic America"

(GSR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

When it comes to helping immigrants, Catholic sisters are one of the few constants in a tempestuous American landscape often shaped by hostility and division.

"They are invested in the marginalized and dispossessed," said Margaret McGuinness, a religion professor at La Salle University in Philadelphia and author of Called to Serve: A History of Nuns in America. "It's something rooted in their mission." She noted that many sisters were immigrants themselves.

Sisters have been active from coast to coast as national leaders have come and gone and as anti-immigrant sentiment has ebbed and flowed.

Congressional legislation addressing the status and rights of immigrants has passed and, in an increasingly polarized political environment, failed to pass.

The Trump administration was hotly criticized for its draconian policies. But the months-old Biden team has recently struggled to handle the surge, particularly among unaccompanied minors at the southern border.

The work of the sisters continues across geographical boundaries, noted McGuinness. In Texas, Missionary of Jesus Sr. Norma Pimentel works with new migrants in the Rio Grande Valley. On another side of the country, in New York City's Lower East Side, Cabrini Immigrant Services, founded by the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, provides legal and social services to the city's immigrant community.

Though some are willing to practice civil disobedience or battle hostility one on one to support new arrivals, sisters are more likely in the 21st century to leverage the power of the institutions they themselves founded.

A religion professor at La Salle University, Philadelphia, Margaret McGuinness says that American sisters have always had the same mission: to work with those on the margins. That includes many immigrants. She is pictured in 2017 giving a presentation at the "Too Small a World" conference at the University of Notre Dame. (GSR file photo/Dan Stockman)

A charism spanning centuries

Nineteenth- and early 20th-century nuns, often immigrants themselves, had to counter anti-Catholic prejudice but were embraced in the end by a country that welcomed the hospitals, orphanages and schools sisters created, often in places where none had previously existed.

Now many sisters offer direct services or human rights advocacy for migrants and refugees who have become targets of suspicion and disdain.

When it comes to supporting immigrants, suggested Sr. Verónica Fajardo, her congregation, the Sisters of the Holy Cross, is just doing what it's been doing since 1875, when the nuns first arrived in Utah. In those days, they opened hospitals and orphanages as well as provided help for miners.

"Here in Utah, the older sisters remind me, we're standing on the shoulders of the women who came before us. The way we provide [services] might be different, but the charism is very much alive in our work," said Fajardo.

She's proud, she said, that even the COVID-19 pandemic hasn't stopped the sisters from providing services to the vulnerable populations they serve, both in Park City, where the population she counsels includes undocumented immigrants, and in Salt Lake City, where Holy Cross Ministries is based.

Her own family came to the United States when she was 8, fleeing Nicaragua because her father had received death threats. A licensed clinical social worker, Fajardo now offers help to those in similar circumstances who have come after her.

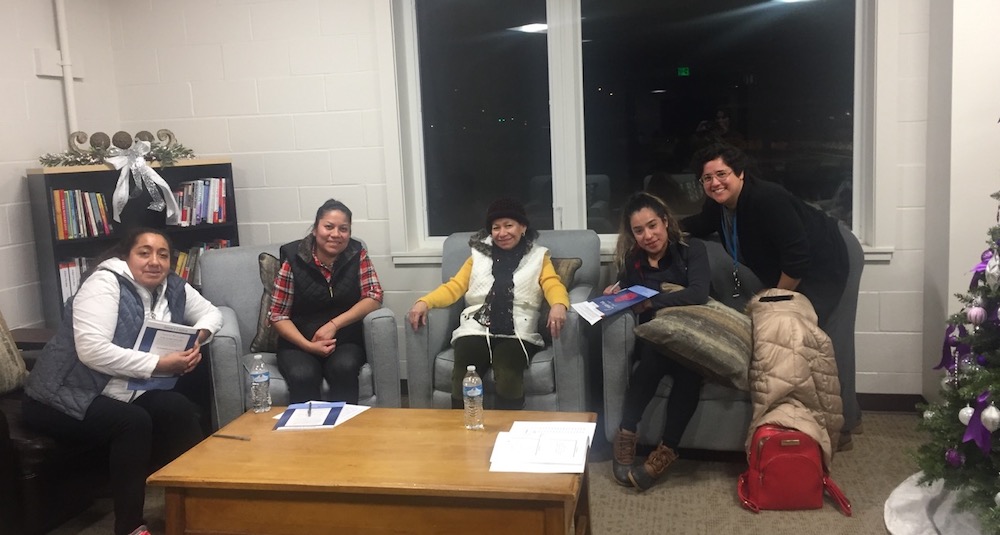

Sr. Verónica Fajardo, at far right, a licensed clinical social worker and member of the Sisters of the Holy Cross, leads a support group sponsored by Holy Cross Ministries in Salt Lake City in December 2019. (Courtesy of Verónica Fajardo)

Though many associate the Utah town with affluence and the Sundance Film Festival, she said, lots of immigrants work in Park City, while enduring lives in the shadows and the impact of ongoing prejudice. That includes being the object of degrading comments and discrimination.

The result?

Immigrant crime victims often don't call the police, and victims of domestic violence sometimes remain silent, she said. She sees clients with high levels of anxiety and depression. "You can only hold it in for so long, then it all falls apart."

Fajardo, who encourages her younger clients to finish high school and not to drop out of college, said she hopes the Biden administration will provide new opportunities for the immigrant population she and her companion sisters serve.

Now, under the new administration, Fajardo wrote in an email, "I think they are hopeful to hear that the DACA program [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] is continuing and there have been discussions about trying to work on a law to help Dreamers. They were quite nervous before that it would go away and they would be left with nothing."

With all the difficulties, her clients tell her, life is still better in the United States than in their home countries.

Advertisement

Persistent hostility to other cultures

Many sisters seem acutely aware of the hostility migrants can encounter, particularly those who are undocumented.

"The bottom line is some people are not accepting of people from other cultures," said Sr. Cecilia Cyford, a Sister of St. Joseph and a religion coordinator for Sacred Heart Parish in Glyndon, Maryland. She has been involved with Baltimore's Asylee Women Enterprise since its founding in 2011. The agency, also known as AWE, is a secular organization that provides wraparound services to asylum-seekers and is supported by six Catholic women religious communities and other faith groups.

More than 30 years ago, Mercy Srs. JoAnn Persch and Patricia Murphy helped found Su Casa Catholic Worker Community in Chicago for Central American immigrants who had faced violence and oppression in their own countries.

"It was probably the hardest time of our lives, but we wouldn't trade it for anything," Persch said.

In 2012, the duo, well known in the Chicago area for their persistence in spotlighting the needs of migrants, also helped found the Interfaith Community for Detained Immigrants. Veterans of years of vigils outside Broadview, an ICE detention facility in Chicago, Persch and Murphy have made trips to Washington, D.C., to engage in nonviolent protest for immigrant rights in the Capitol Rotunda — and have been arrested in the process.

St. Joseph Sr. Cecilia Cyford, center, at head of desks, is a member of one of the founding communities that helped launch Baltimore's Asylee Women Enterprise. She is the coordinator of religious education at Sacred Heart Parish in Glyndon, Maryland, home to immigrants of many nationalities. (Courtesy of Cecilia Cyford)

Murphy and Persch, who fought for years to gain access to migrants in detention centers, have a motto: "We do it peacefully and respectfully. But we never take no for an answer."

Persch speculated that the Mercy sisters who arrived in 1840s America might have had an easier time entering the country than the people she serves now — refugees who walk and swim and sometimes ride on top of trains in their efforts to cross the U.S.-Mexico border.

As new arrivals, 19th-century nuns often faced a suspicion of Catholics on the part of American Protestants. On the other hand, they sometimes worked with evangelical fervor to keep Catholic immigrants in the fold. Those Protestant-Catholic divides have largely ebbed with the passing of the years.

An evolution of partnerships

Now, sisters like Persch often collaborate, not only with other Christian groups, but with Jewish and Muslim organizations, as well.

"We are all gathered around our belief that whatever faiths we have, we are challenged to welcome the stranger, to treat everyone like a child of God, with dignity and respect," Persch said.

Recalling her days as a young woman in the convent, she said, "in those days, you didn't go out into the community and didn't interact. It's just been a wonderful experience."

As associate director of the Franciscan Action Network, Sr. Marie Lucey, of the Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia, works collaboratively with the Justice for Immigrants campaign of the U.S. bishops' conference and with the Interfaith Immigration Coalition.

"Working with partners is very, very essential to what we do as a multi-issue organization," Lucey said.

Mercy Sr. Pat Murphy, left, celebrates her 90th birthday on April 20, 2019, with Mercy Sr. JoAnn Persch and Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Illinois, in Chicago. (Courtesy of JoAnn Persch)

Supported by the information gathered and analysis done by their partner organizations, the Franciscan Action Network addresses issues around asylum, the status of refugees, deportation and the root causes of immigration, including the role of the United States in Central American conflicts.

At the request of the local bishop, 19th-century Franciscan women religious worked with immigrant German children who were unwelcome in public schools, Lucey said.

Catholics of that era faced hostility from, among others, the nativist Know-Nothings, a party that promoted the idea that immigration posed a growing threat to the welfare of U.S.-born Protestants. But "sisters themselves were often warmly welcomed because they saw the good work that we were doing," Lucey said.

Nevertheless, "there are a lot of anti-immigrant forces still at work today in our country," she said, suggesting that anti-immigrant sentiment had been present through much of American history.

Instead of seeing each other as threats, she said, 21st century people of faith collaborate to help immigrants. "It's a world of difference. We highly value our interfaith community. For those of us who work in the area of justice, we don't get into our differences in theology. That's not the focus."

Presentation Sr. Sharon Altendorf is active in the Interfaith Welcome Coalition, a San Antonio-based organization founded by a Presbyterian minister to assist unaccompanied children coming from Central America. It has now expanded its mission to help refugees and other vulnerable populations. Though she's retired, the sister also teaches English-as-a-second-language classes at the Presentation Ministry Center.

Sr. Sharon Altendorf, a member of the community of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, left, says goodbye to Jader Reyes of Nicaragua, after giving him food and mapping his travel itinerary on June 14, 2019. (GSR file photo/Nuri Vallbona)

The people she works with are "constantly being discriminated against and challenged," said Altendorf, who said that 14 years of working in Peru had helped her understand what it was like to be a foreigner. "Isn't it awful that we look for a scapegoat?" she asked. "People are afraid they are going to lose their status. Those who have been put down a lot will be someone who puts down another person, unless we get something to change in our lives."

Her own congregation, the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, originally came from Ireland to work with the children of Irish immigrants. A congregation composed of many separate communities, Presentation sisters also ministered to immigrant farmers in the Dakotas and elsewhere, Altendorf said.

Whether they are lobbying Congress on behalf of the DACA "Dreamers," teaching English as a second language, or finding housing for immigrants released from ICE detention, sisters say that they are part of a bigger picture, one drawn by the women who arrived on these shores more than a century ago with the same dream.

"When you read our history, our sisters have ministered to everyone in need," said Cyford, adding that includes people who are considered unacceptable or rejected by others.

Mentioning a saying often used in her community, Cyford said, sisters are always "ready for any good work."