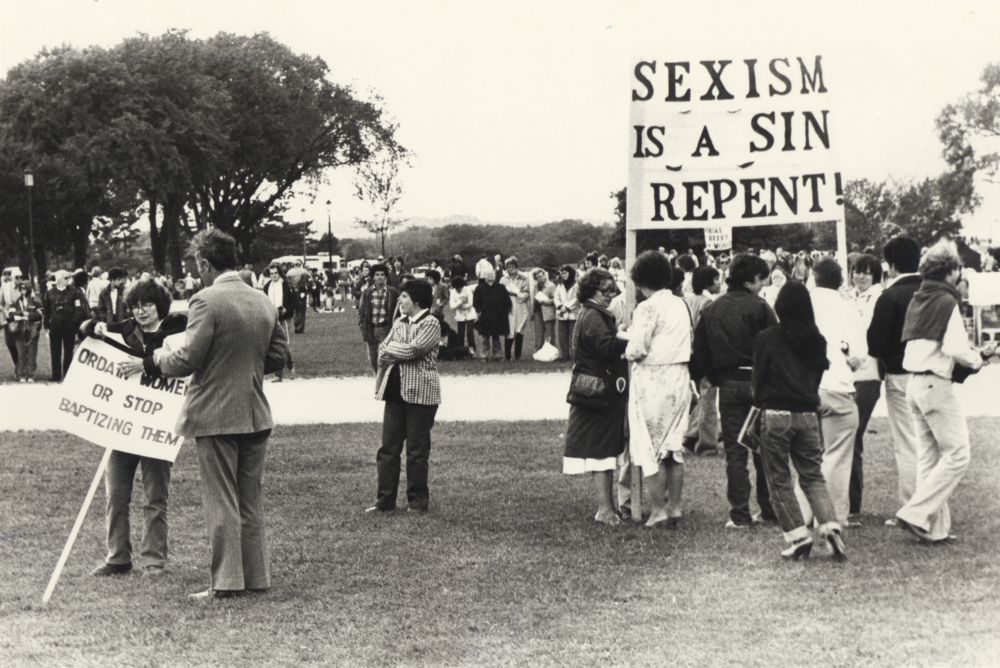

Catholics rally for women's ordination on the National Mall during Pope John Paul II's October 1979 visit to Washington, D.C. (NCR photo/Mark Winiarski)

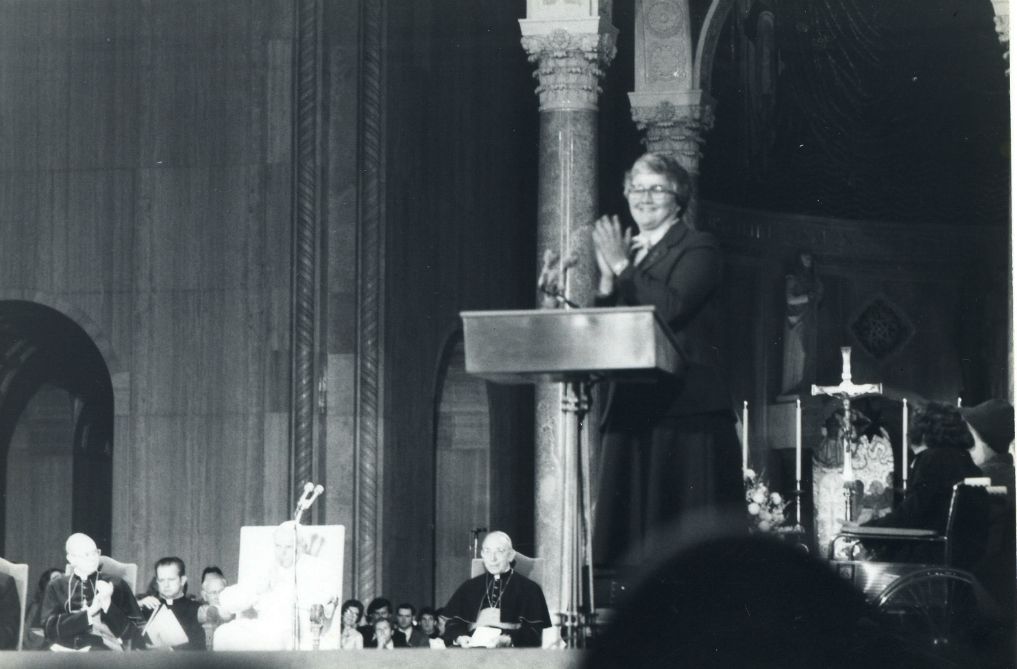

On an October day four decades ago, Sr. Theresa Kane, president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious and head of the Sisters of Mercy in the U.S., stood before 5,000 other sisters gathered to greet Pope John Paul II at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. She spoke of the sisters' "profound respect, esteem and affection" for the pontiff.

Then Kane uttered these memorable words: "Our contemplation leads us to state that the church in its struggle to be faithful to its call for reverence and dignity for all persons must respond by providing the possibility of women as persons being included in all ministries of our church. I urge you, Your Holiness, to be open to and respond to the voices coming from the women of this country who are desirous of serving in and through the church as fully participating members."

Kane's televised statement, a politely worded but direct challenge to the pontiff, drew intense media coverage. Just days before, in an address to an audience of vowed religious men and women in Philadelphia, John Paul had reaffirmed the ban on women priests, saying that an all-male priesthood "was the way that God had chosen to shepherd his flock."

But many American nuns and some Catholic laypeople saw a pressing need for the church to reform itself. For sisters, in the wave of enthusiasm that followed the Second Vatican Council, "there was a sense of hope that change was going to come, hope for reform. Change was coming, and the sisters could be a part of the change," said Sandra Yocum, associate professor of religious studies at the University of Dayton, in an interview.

Mercy Sr. Theresa Kane, president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, addresses Pope John Paul II on Oct. 7, 1979, at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington during the pope's visit to the United States. (Courtesy of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious)

Forty years after Kane attracted worldwide notice for her outspoken challenge, sisters have not stopped pressing for denominational reform. Despite the lack of progress on women's ordination, some sisters see signs of hope in the advancement of women religious and other laypeople to leadership roles. They are also heartened by the pastoral approach of Pope Francis, who shares their desire to dismantle clericalism and create more decision-making roles for laity.

In June, Francis appointed four women, three of them women religious, as consultors to the general secretariat of the Synod of Bishops, a first. In July, he tapped six superiors of women's religious orders and a consecrated laywoman to serve on the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life.

But while Kane agrees that the church has made strides, the lively nun, who had once predicted the Catholic Church would ordain a female priest by 2000, is today less sanguine about female ordination.

"I guess I anticipated they would move a little more smoothly, and try to move on," Kane said in an interview, referring to bishops and popes who have said women's ordination is not possible. "There's something really seriously wrong with our church. I don't think men want to see women as priests. It's a great loss to our church. They will regret it someday."

Kane spoke on behalf of a group of women who, since the days of Vatican II, had made an increasingly spirited bid to exercise more authority in the church. In 1965, a predecessor organization, the Conference of Major Superiors of Women, had formed a committee on canon law so that women could have a say in the legal code that governed the church. When the conference adopted new bylaws in 1971 and changed its name to the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR), said Loretto Sr. Jeannine Gramick, the Vatican initially refused to acknowledge the new name. "They knew the women in the United States were becoming uppity," said Gramick, who has attracted Vatican scrutiny herself over advocacy for LGBT Catholics.

Mercy Sr. Theresa Kane at the summer professions of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas (Courtesy of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas)

In 1975, LCWR was one of 49 groups and individuals endorsing the newly-formed Women's Ordination Conference, said Sr. Christine Schenk, a Sister of St. Joseph and author of the forthcoming book To Speak the Truth in Love: A Biography of Theresa Kane, RSM in an email. (Schenk is a columnist for National Catholic Reporter and was recently appointed to NCR's board of directors.) Over the years, many sisters had also shed their habits for suits or simple dress, had taken to heart to minister to those on the margins, and changed their internal congregational structures to be less authoritarian and hierarchical.

The conference's leadership had requested a meeting with the pope during his 1979 U.S. visit but had not been granted one. Kane said she hoped to make four points in her brief address: They included greeting the pontiff, acknowledging the work of the sisters, expressing solidarity with the poor, and a request that women be included in all church ministries, she said.

The plea for equality in the church, which still resonates in 2019, embraced all Catholic women, said Kane. "We're promoting not just sisters, but women, women who have been the strength of the church for so long."

Kathleen Sprows Cummings, director of the University of Notre Dame's Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism (Courtesy of the Cushwa Center/Terry Trethewey)

Women a central issue

The "open season on women religious" in the U.S. that followed, suggested feminist theologian Mary Hunt in an interview, could be traced to that moment in the basilica. Hunt is co-director of Women's Alliance for Theology, Ethics and Ritual.

Indeed, skepticism about the theological orthodoxy and intentions of American sisters would linger for decades, erupting in controversies years later involving individual sisters, investigations, apostolic visitations and a doctrinal assessment of LCWR by a suspicious Vatican.

"When you read the statement, it was very deferential," said Kathleen Sprows Cummings, director of the University of Notre Dame's Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism. "It was hardly a feminist manifesto, but it's hard to believe the sensation it caused."

A group of about 50 sisters adorned with blue armbands scattered through the basilica stood throughout the pope's speech in silent protest. Outside, laywomen handed out pamphlets to the crowds explaining what the sisters were doing inside. While Kane was aware of their plans, she had made her own separately, keeping the contents of her address to herself. "Some sisters were very annoyed we were standing," recalled Gramick, one of the sisters wearing an armband. "My recollection is most sisters were very glad. They felt as we did. Women in the church were becoming very much aware of our second-class citizenship and the fact that we didn't have a voice."

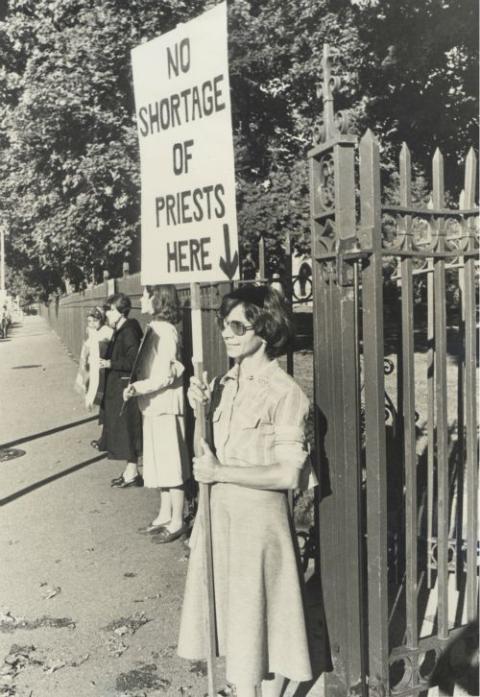

Members of the Boston Women's Ordination Conference pickets men's ordination Sept. 15, 1979, in Newton, Massachusetts. (NCR photo/Harry Brett)

"Theresa's remarks drew a line in the sand," said Sr. Doris Gottemoeller, then serving on the Mercy leadership team alongside Kane, and responsible for helping to handle the media frenzy that followed. Women's place in the church "became not just the passion of a few on the fringes. We could not say that anymore. It was the central issue."

Other Christian denominations, including the United Methodist Church and a part of what eventually became the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), had been ordaining women since the 1950s. In the 1970s, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Episcopal Church began to do the same.

Kane's words were also a wake-up call to the Vatican. "Everything had gone smoothly," she recalled of that October day. "What I was saying surprised them [Vatican officials]. It got such worldwide coverage. It made them anxious."

In November that year, she was asked to explain her statement during an already scheduled trip to meet with Vatican's Sacred Congregation for Religious and Secular Institutes (later renamed the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life). She made it clear in that meeting, Kane said, that while she hadn't explicitly mentioned the word "ordination," she was asking that women be included in all aspects of church leadership and was not excluding ordination.

The basilica address by Kane got Rome's attention for several reasons, said Hunt. "They learned Catholic women could and would think for themselves."

Mercy Sr. Doris Gottemoeller at St. Mary Academy in Providence, Rhode Island, in August (Provided photo)

The Mercy sister was also highly regarded. "It wasn't some dissident person; it was someone who acted and felt and spoke in a very professional and poised way … in a way that made her act like an equal to the pope. This was not something that popes experienced."

Other sisters years later would advocate for female ordination — and be removed from church-affiliated posts. In 1995, Mercy Sr. Carmel McEnroy, a tenured theology professor at Indiana's St. Meinrad School of Theology, was dismissed from her position for "public dissent." McEnroy and about 1,500 others had signed an open letter to John Paul II opposing his ban on women priests. She received public support from her colleagues in the American Association of University Professors, and a lawsuit against the school was eventually dismissed, the judge arguing that the court didn't have jurisdiction in religious affairs.

In 2008, Sr. Louise Lears, a Sister of Charity, was banned from all church ministries in St. Louis, Missouri, by Archbishop Raymond Burke, in part because she had attended a women's ordination ceremony that was secretly recorded by the archdiocese, according to an NCR article. Both McEnroy and Lears declined to be interviewed for this article.

Lingering inquiries

Women religious congregations in the U.S. were scrutinized by the Vatican in a draining, years-long apostolic visitation. LCWR suffered its own share of negative attention both from the Vatican and local bishops. As Pope Benedict XVI's time* in the Vatican drew to a close, a years-long Vatican "doctrinal assessment" asserted that LCWR had challenged church doctrine and tradition on numerous occasions (a characterization strongly disputed by the organization). Among the supposed offenses: "For example, the LCWR publicly expressed in 1977 its refusal to assent to the teaching of Inter Insigniores on the reservation of priestly ordination to men. This public refusal has never been corrected."

In response to questions about their current stance on women's ordination, LCWR send this statement:

In these last 40 years, LCWR has remained committed to seeking ways to expand the ways in which women may hold roles of leadership and influence in the church. As an example, in 1992 LCWR conducted a major study, entitled Women & Jurisdiction, to understand the ways in which persons who are not ordained may participate in the governance of the Catholic Church, by studying the roles women do hold: chancellor, tribunal judge, finance officer, director of Catholic Charities, vicar/delegate for religious (all diocesan positions) and pastoral director (parish position). Since that time we have continued to use the opportunities we have in meetings with officials of the Vatican and the USCCB [U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops] to raise questions about the inclusion of women in decision-making positions within the church wherever possible. We also applaud the recent inclusion of women as full members of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life (CICLSAL) and see this as a significant advance in bringing women into their rightful place within the church.

Both Vatican investigations — conducted while the child sex-abuse scandal was making headlines in the U.S. — drew the ire of laity who supported the sisters.

Advertisement

Francis, who early in his papacy called for women to play a greater role in church affairs, brought the apostolic visitation to a close in December 2014, and the Vatican oversight of LCWR to an end in 2015.

Not all U.S. nuns agreed with the reformist stance taken by LCWR on women's ordination or other issues. Newspaper articles from 1979 note that some sisters didn't applaud Kane after her address. In 1992, the Vatican approved the formation of the Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious, an alternative conference for sisters in the U.S. who preferred a more traditional approach to religious life, including wearing habits and being "ecclesial women faithful to the Magisterium," according to its core values.

While the bar to ordination has remained in place, women, including sisters, wield substantially more authority in certain spheres of the church than they did 40 years ago.

Mercy Sr. Sharon Euart, associate general secretary of the U.S. bishops' conference, left, confers with Cardinal Joseph Bernardin of Chicago at a 1995 meeting. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

Now head of the Resource Center for Religious Institutes, for instance, Sr. Sharon Euart, a Sister of Mercy, has had a career that exemplifies the strides made. After receiving a doctorate in canon law at Catholic University, she worked at the National Conference of Catholic Bishops and United States Catholic Conference (combined July 1, 2001, into the USCCB) as secretary for planning. In 1989, she was appointed associate general secretary, the first woman to hold the office.

"Recognizing the role of laypeople in the mission of the church is a huge contribution of Vatican II," said Euart. "Women are a part of that. Including laypeople in the life of the church also opened many opportunities for women, including women religious. In a visible way, it has changed the face of church ministry."

Euart also pointed to the 1994 "Strengthening the Bonds of Peace," a pastoral letter in which the U.S. bishops invited others to join with them to "explore new and creative ways in which women can participate in church leadership."

As examples in the U.S., Euart cited a lay woman as chancellor of a large archdiocese, a lay man as director of a diocesan tribunal, a lay woman as chief operating officer of a large women's religious institute, a lay woman as spokesperson for an archdiocese, and lay women and laymen as parish pastoral associates.

Loretto Sr. Jeannine Gramick visits the Vatican on Ash Wednesday, Feb. 28, 2015, on a trip with 50 LGBT pilgrims. (Provided photo)

The question of women's ordination in the modern era is at least as old as the Second Vatican Council. During the papacy of Pope Paul VI, the issue was addressed by the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine Faith in October 1976 in the document Inter Insigniores, "On the Question of Admission of Women to the Ministerial Priesthood." In 1994, John Paul II restated the ban on women priests in an apostolic letter, which Benedict later declared infallible. Francis has reiterated that position.

"He's continued to repeat the positions of John Paul II," said Kate McElwee, executive director of the Women's Ordination Conference. "So, it is discouraging. But we do know that he is a man of transformation and has had his mind changed before."

The ban on priestly ordination means that women are effectively barred from the highest ranks of church leadership, note some.

"We are still far behind where we could be and should be. Since women cannot be ordained as priests, they are effectively shut out of most of the important leadership positions in the hierarchical church," said Jesuit Fr. James Martin, editor at large for America.

Sandra Yocum, associate professor of religious studies at the University of Dayton (Provided photo)

Though the committee studying the history of women deacons in the church wasn't able to come to a consensus, the door to ordaining women deacons has not been shut. "It seems obvious to me that it's the way to go," said Kane, about women deacons.

Gramick, who has had her own struggles with the Vatican under John Paul II, praised the current pope's emphasis on "synodality" as a hopeful sign. Though the synod of bishops was started by Paul VI to shore up the relationship between the pope and bishops around the world, Francis has expanded the meaning of the word in practice to embrace the voice of laity.

"It's a sign that we are moving out of the dark ages into a more participatory, democratic form of governance," she said.

Catholic sisters laid down a challenge to the church that went beyond ordination, suggested Cummings. "They want to transform the priesthood. They don't just want a seat at the table. They want to rearrange the seating, in sense, by reducing clerical privilege, by focusing on ordination as more a call to serve than a pathway to power."

*An earlier version of this story used the incorrect Roman numerals in the name of Pope Benedict XVI.

[Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans is a freelance religion writer in the Philadelphia area.]