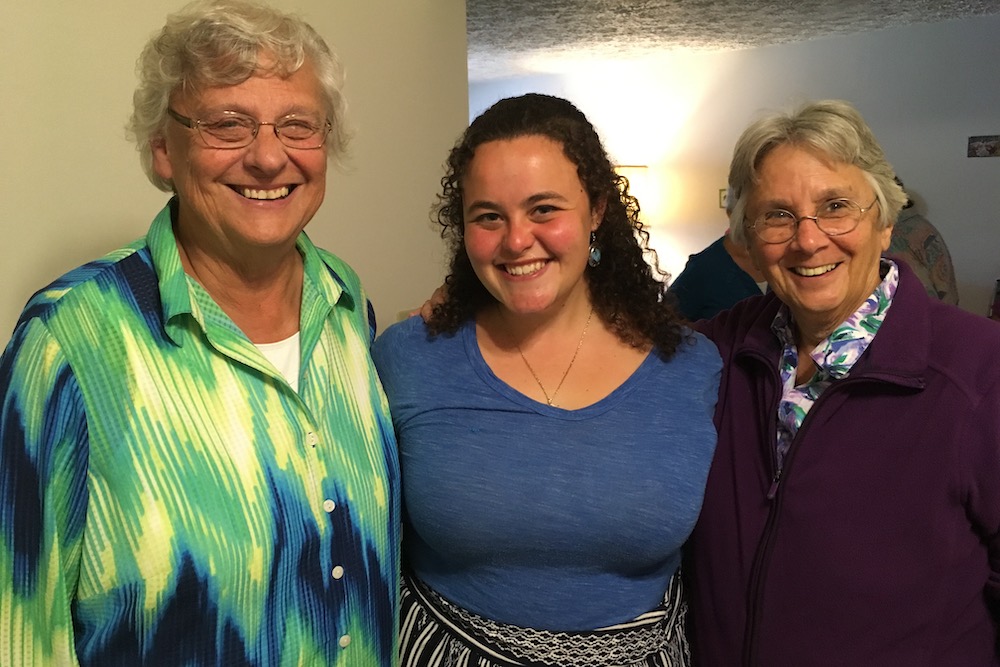

Benedictine Sr. Mary Lou Kownacki, Jacqueline Sanchez-Small and Sr. Mary Miller at a housewarming party. (Breanna Mekuly)

The Rule of Benedict says that, in the monastery, we shouldn't rank ourselves by age or social status, but by the amount of time that we have spent in the community. By that metric, I'm the second "youngest" out of our 89 sisters. But by the very human, unavoidable metric of chronological age, I am definitely the baby as a newly-minted 27-year-old. While there's a sizable contingent of young-to-middle-aged people here, like most communities of U.S. women religious, the bulk of us are concentrated in their 70s and 80s, with a few in their 90s and beyond.

People always want to know what it's like, being the youngest around here. "Do you feel like you're living in a nursing home?" they ask me. "What do you talk to them about?" "Do they patronize you?" "Do you drive them nuts?"

We have our generational differences, sure. Some can't fathom what it was like for me to grow up with divorced parents, in a country that's been at war since I was in grade school, to never have known a world without car radios or microwaves. It's hard for me to imagine their early years, too, and I'm always asking for stories about the 1950s and Renewal. Sometimes I talk too quietly for them to hear what I'm saying, or I charge out into a freezing cold day with no mittens, no hat, no scarf, and they shiver just looking at me. Sometimes I'm sitting with the bottoms of my shoes on a couch, or picking at my cuticles, and they wonder if the world has totally lost its sense of etiquette.

Advertisement

But by and large, generational differences aren't so wildly important as they might seem. We have a sense of a common purpose, for the most part, and our day-to-day lives all flow along the same lines in the monastery. For the most part, we like and love each other enough to look past the foibles that come with being 27, or being 87.

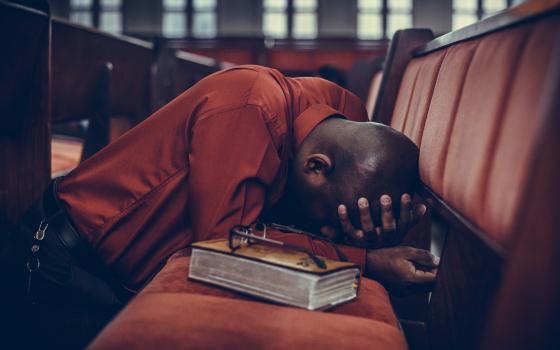

I'll let you in on the secret of what is really hard about being one of few young people in the monastery: My sisters get sick, and they die. And they'll keep on getting sick and dying.

There is, I've come to learn, something very beautiful about death itself. Keeping vigil with sisters in their final moments, and joining the community in our funeral rituals has shown me that, right alongside the sadness you'd expect to find, there is a great sense of peace, of completion, of comfort in knowing that our sister is now free from suffering.

But still… they're gone. Traces of them linger around the monastery: one's prayer book, embossed with her name, sits at her old place in chapel; the smells of another's best recipes waft from the kitchen; a portrait of another is on display, sketched by a postulant. It's an incredible mystery, and one that I can't seem to look away from, as though if I just think about it a little bit harder, I'll understand where it is that they've gone, these women whose holiness and constancy helped to weave the tapestry of life here for decades.

I am not particularly worried about the future of our community, although I know we have our share of hard transitions ahead. I figure there will always be people who want to center their lives in seeking God, accompanied by others, and so monastic life will continue. But I do worry about the losses that stand ahead of us, the years that are not just coming but already here, when I'll say goodbye to the women who are shaping me and pointing me toward God.

Erie Benedictines and friends celebrate at a local restaurant. Pictured left to right, front to back are: Stephanie Ciner, Sr. Anne McCarthy, Sr. Stephanie Schmidt, Sr. Val Luckey, Sr. Ann Muczynski, Jacqueline Sanchez-Small, Sr. Mary Ellen Plumb, Katie Gordon, Erin Carey, and Sr. Linda Romey. (Provided photo)

Loss has always been a part of this kind of life. The sisters who came before me buried their friends and mentors, too. But because of that darned age difference, there is a particular sorrow in knowing that the bulk of my community will not be here when I am middle-aged. I'm jealous of sisters who, at their jubilees, could look across the chapel and smile at their novice director. My friends who are in their 60s and 70s now — where will they be in 20 years, when I'm 47? Who will I turn to for guidance, then? And who will tell me to get my elbows off the table and put on snow boots? Who will the other young sisters and I look to for wisdom in challenging moments — when deciding to start or close ministries, managing our property, navigating our personal struggles?

Other friends, new mentors and younger sisters will come along, I know. Life will be "changed, not ended." But it's still painful to consider.

At the same time, I do profess a Christian faith. I believe in the communion of saints. I say, every Easter, that death has lost its sting, has been swallowed up in Christ. I'm not sure that means that our loved ones are "looking down on us," answering me when I plead with them to help me find my keys, or to fill me with patience and compassion. Maybe it means something a little more abstract, but no less real.

A few months ago, I was telling someone about the alcove at the monastery where we keep furniture and mattresses that aren't being used. It's called "Anselm's Attic," and I was explaining that "it's named after our sister, Anselm ..." and going into the story of her connection to it. One of the 70-something sisters broke into the conversation with a big smile. "Do you know how much it means," she said, "to hear you say, 'our sister, Anselm,' when she died before you were born or thought of? To know that you know something about her, remember her, talk about her?"

Benedictine Sr. Christine Kosin, Jacqueline Sanchez-Small, and Benedictine Sr. Rosanne Lindal-Hynes chat in the monastery office. (Sr. Val Luckey, OSB)

This is the heart of intergenerational life, I think: that I do feel a real sense of kinship with the women who came long before me, whose names and tiny fragments of their stories are all that are known to me. It's not that I think that they were purely perfect, icons that I won't ever live up to: Some were troubled, or short-tempered, or immature, just like I can be. But like my sisters who are here with me today, they shared a common purpose with me, and they worked hard to lay a strong foundation for the life we have at the monastery now. I draw strength from the stories of what they had to overcome, the obstacles they faced and the ways they managed to make life meaningful, joyful.

Those sisters do feel present to me. And I hope that the ones I have here now will still feel like a part of this community decades from now. I think they will, as long as we keep listening to each other, as long as they keep sharing their stories with me so generously, as long as — some day in the future — I'm able to tell some new seeker here about the vibrant women who came before her, about their faith, about the God they were seeking.

After all, for all these centuries we've been praying with the psalmist:

I will sing of your love, O God;

through all generations,

I will proclaim your faithfulness.Of this I am sure —

that your love lasts forever,

your faithfulness is firmly established. (Psalm 89)We heard for ourselves, God,

all that you did in days past;

those before us have told us the story. (Psalm 44)

[Jacqueline Sanchez-Small is a postulant of the Benedictine Sisters of Erie, Pennsylvania. Before entering the community, she received a master's degree in divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary and a master's degree in social work from Rutgers University. She now works for Benetvision and Monasteries of the Heart, outreaches of the Benedictine Sisters of Erie that offer contemporary monastic spirituality to seekers around the world.]

Editor's note: Some of this material appeared in another form in the writer's blog, Little Blog for Beginners, on monasteriesoftheheart.org.