Georgette Gregory, of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto, checks a patient’s blood pressure on the Health Bus. Gregory spent 18 years working as a nurse on the Health Bus Program, run by Toronto's Sherbourne Health Center. (Courtesy of Sherbourne Health Center)

In the late 1990s, the inner-city Kings Cross neighborhood of Sydney, Australia, had one of the highest counts of drug overdoses in the country. Australian Sister of Charity Annette Cunliffe says shopkeepers in the neighborhood had to sweep up needles from outside their doors daily and call ambulances at "all hours of the day and night."

The Sisters of Charity, who since 1870 have operated St. Vincent's Hospital in the Darlinghurst neighborhood bordering Kings Cross, proposed creating a medically supervised injecting center at St. Vincent's in response to the crisis. An injecting center, also called a "safe injecting site," is a secure, indoor environment where intravenous drug users can have access to clean needles, along with medical supervision and treatment, in case of overdoses.

On-site access to rehabilitation and counseling are also available. No drugs would be provided at the St. Vincent's injecting room, and only regular drug users would be admitted — someone who wanted to try for the first time would not be allowed.

The St. Vincent's supervised injecting center, a radical concept then and still considered so today in many parts of the world, was to be the first in Australia and one of the first in the world. (The first opened in Switzerland in 1986.) Proposed as an 18-month trial, the sisters' plan was approved by the state Parliament of New South Wales in 1999 and they began working towards opening the center.

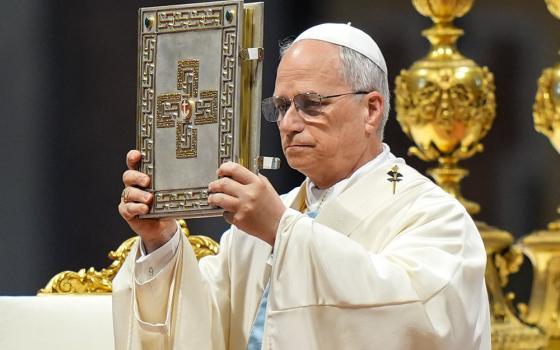

Annette Cunliffe, of the Sisters of Charity of Sydney, Australia, worked to set up a safe injection site for intravenous drug users in 1999. (Courtesy of Sisters of Charity, Australia)

Many of the area's residents welcomed the center because it would be likely to take drug use off the streets. Neighbors frequently "had to step over or around somebody who was passed out from drug use on the street," Cunliffe says. "People were even dying on the streets."

But not everyone was supportive. Some members of the larger Catholic community requested that the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith rule on the proposal. The result? The sisters' planned center could be considered an "extremely proximate" material cooperation in evil and was "not acceptable." The sisters, reluctantly, withdrew their plan.

While the Sisters of Charity had weighed those concerns themselves and "were all uneasy about [the injecting room] to some extent," Cunliffe recalls, they had come to the decision together that, despite the reservations, the program would have been in alignment with their charism of service for the poor.

"They said it was cooperation with evil and, I mean, it is. It is. But there are times when you have to consider the person rather than the sin."

Global reach

In the end, the injecting room in Kings Cross did open — in 2001, without the sisters' involvement. Instead, it is run by the Uniting Church of Australia, which took the research the Sisters of Charity had compiled and continued developing the plan for implementation from there. Staffed with a medical doctor, registered nurses (including a mental health nurse), counselors, and security guards, the site has supervised over one million injections with no fatalities to date.

Since the pioneering efforts of the Sisters of Charity in Sydney, an estimated 100 safe injecting sites have opened in multiple cities worldwide, mostly throughout Europe and Canada. A 2014 review of 75 studies done on safe injection sites found them to be successful in reducing overdoses and increasing access to health services for users. In other words, the sisters did manage to fulfill their harm-reduction goals, though indirectly.

In Vancouver, British Columbia, InSite, North America's first safe injection site, was established in 2003 and is used by about 700 people each day. Since then, about 25 total sites have opened across Canada.

Two of the sites are tied to Catholic institutions: There is an injecting room operated by Providence Health Care at St. Paul's Hospital in Vancouver, founded by the Sisters of Providence; and in Toronto, the city's largest Catholic hospital, St. Michael's, founded by the Sisters of St. Joseph, does not have its own site but collaborates with many in the area.

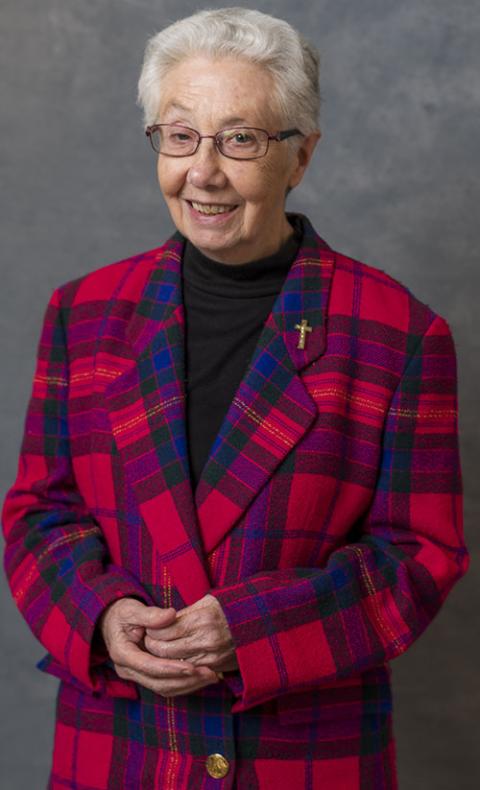

"I feel the safe injection sites are absolutely essential to keep people who are addicted with clean supplies to help keep them from becoming ill with dirty needles," says Sister of St. Joseph Georgette Gregory. Gregory, who spent 18 years working as a nurse on the Health Bus Program, run by Toronto's Sherbourne Health Center. According to Sherbourne Health's website, the Health Bus is a mobile unit based in Mid-East Toronto, a densely populated neighborhood with a high number of services for individuals experiencing homelessness.

In addition to illness treatment and wound care, the Health Bus provides addiction counseling and drug harm reduction services to patients, including distributing clean needles and other materials in "safer injection kits."

Distributing clean syringes to injection drug users, in what is known as a "needle exchange program," is another harm-reduction measure, similar to safe injection sites but considered by some to be less controversial from a Catholic ethics standpoint. With needle exchange programs, which involve giving clean syringes to drug users and picking up used needles in exchange, "the case is easier to make that one is simply being sure that the person is as free as possible from the infections that can be associated with reusing needles," explains Daniel P. Sulmasy, a medical ethics scholar and former Franciscan friar who wrote a paper about this topic. "To provide a space in which people are able to inject the drugs can, I think, make it seem more as if one is providing shelter and supporting them in their behavior rather than simply trying to make sure that, if they do this, they are not doing it in a way that is unsafe."

During her years working on the Health Bus, Gregory says she referred many clients to safe injection sites run by Toronto's Public Health Department, and needle exchange programs run by community health centers. When nursing and social work students came to the Health Bus to learn about treating vulnerable populations, Gregory linked them up with the leader of a local needle exchange program. "I thought it was important for the students to learn about drug addiction and what helps," she says.

Gregory also set up a sharps container outside Mustard Seed, a community center run by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto, so drug users could safely dispose of used syringes, resulting in fewer needles on the street. She says some sisters were in agreement with safe injection sites and needle exchange programs while others "thought it was encouraging drug use."

Sister of St. Joseph of Toronto Georgette Gregory outside the Health Bus (Courtesy of Sherbourne Health Center)

Material cooperation

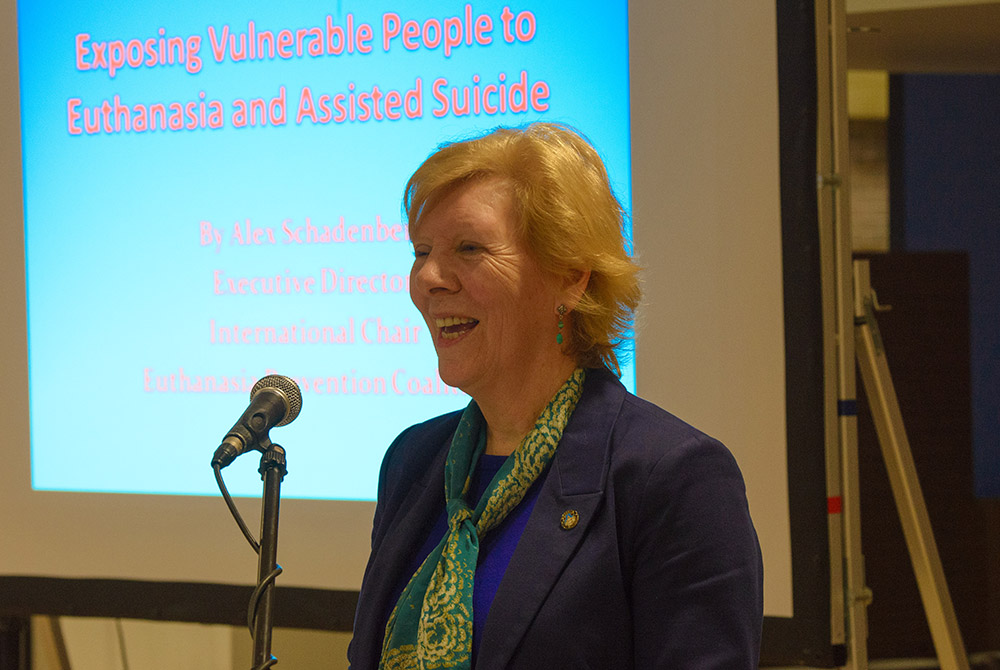

"It's a genuine concern that you might be doing the wrong thing," admits Moira McQueen, executive director of the Canadian Catholic Bioethics Institute. McQueen was tapped by leaders from St. Michael's in Toronto to provide a moral theology perspective when they were considering whether to get involved with safe injection sites. Citing data that safe injection sites prevent deaths (this May 2019 article from Governing: The Future of States and Localities reported no one has died at a safe injection site anywhere in the world), McQueen told St. Michael's she was supportive of the sites.

There is concern from some Catholics that safe injection sites enable drug use, as the Sydney Sisters of Charity found out when the Vatican ruled their program constituted material cooperation in the "evil" of drug use. But when it comes to material cooperation, McQueen says, the official teaching on it is that if there's a justifying reason, you can be involved. "I think in this particular situation the justifying reason is to save lives," she says. It's significant that safe injection sites do not provide the drugs themselves — a distinction that McQueen says would put them over the edge toward qualifying as formal cooperation and "completely wrong."

"Once you're dead because of a dirty needle, it's a pretty hefty price to pay for wrong — or you could call it 'sinful' — behavior," she says. The scriptural directive to "love your neighbor" forms much of the basis for her thinking. "People disagree about what that love means," she says, but her interpretation of it from a health care perspective is, simply, "you're trying to help people live. You do all you can to save that life. Sometimes it takes measures that are apparently unorthodox." Safe injection sites, she adds, are "very Catholic in terms of protecting life from conception until natural death."

The debate in the United States

There are at least 300 needle exchange programs operating in about 30 U.S. states, according to Healthline Media. In Albany, New York, Catholic Charities established a needle exchange program in 2010. Sister of Mercy Maureen Joyce, CEO of the diocese's Catholic Charities office, told the National Catholic Register at the time that she viewed it as "an extension of our mission to serve the poor and vulnerable." Joyce passed away later that year, but the program, called Project Safe Point, is still run by Catholic Charities today.

Moira McQueen, executive director of the Canadian Catholic Bioethics Institute, advised Catholic Hospitals in Toronto, Canada, about safe injection sites from a moral theology perspective. (Photo by Michael Swan, The Catholic Register; Courtesy of Canadian Catholic Bioethics Institute)

Despite the numerous needle exchange programs, so far there are no safe injection sites. The United States currently experiences 3.5 times as many deaths from drug overdoses than do other high-income, peer countries, researchers from the University of Southern California found in a 2019 study. Safe injection sites, which have been proven time and again to prevent overdose deaths by virtue of the trained medical staff onsite, could be a straightforward solution to this most tragic angle of the crisis.

Yet, while safe injection sites have been approved by local governments in a small handful of U.S. cities, so far none has managed to manifest (aside from one secret, illegal site in an undisclosed location). In Philadelphia — where unintentional drug-related deaths increased from 311 in 2003 to 1,217 in 2017, according to the city's February Opioid Misuse and Overdose Report — lawmakers granted approval for privately operated safe injection sites back in 2018, but critics have consistently blocked them from opening. One of the most outspoken critics of safe injection sites has been Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput, who wrote in a column on Catholic Philly last year that "enabling others to use illegal, life-threatening substances clearly violates divine law."

Other strong opposition to the opening of a safe injection site in Philadelphia has come from neighbors in areas where the sites have been planned to open, according to reporting by Filter.

As reported by WHYY, in February, after a yearlong court battle over whether the Safehouse plan in South Philadelphia "would violate the section of the U.S. Controlled Substances Act commonly known as the 'crackhouse statute,' which makes illegal any space maintained for the purpose of using illicit drugs," a federal judge issued a decision in favor of Safehouse, granting them permission to move forward with their plan. However, after a series of tense community meetings resulting in the building owner pulling out of the lease, Safehouse has paused its plans to move forward with the site for the time being.

Advertisement

Sulmasy, the medical ethics scholar and former Franciscan friar, pushes back against "not in my backyard" concerns. "The question for the Christian is who is my neighbor?" he told Global Sisters Report. "And what we have to say is that the person who is addicted and injecting drugs is my neighbor, and my neighbor will be in my backyard."

While the debate about a safe injection site in Philadelphia continues, a local organization called Prevention Point has been operating a needle exchange program since 1991. Prevention Point also operates an overdose reversal training program, which teaches members of the community how to use Naloxone, a medication that reverses an opioid overdose. A representative from Prevention Point confirmed that multiple women religious in Philadelphia have undergone the training.

Pandemic-related obstacles

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended every area of life, and drug harm reduction programs are no exception. Toronto's Health Bus services, for example, have been halted until further notice, according to their website. In Sydney, the Kings Cross injecting room is still operating but at half capacity. Furthermore, they have had to restrict gatherings in the after-care area, where providers can typically connect more deeply with clients.

"COVID-19 will disappear. One way or another, all epidemics disappear," says McQueen, the moral theologian. But the problem of drug addiction "is an ongoing problem. It will still be there. It's unfortunate but true, it will still be there."

[Georgia Perry is a journalist based in Denver.]