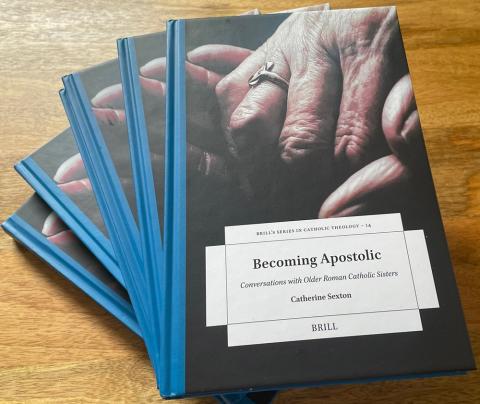

Displaying a sister's profession ring are the hands of a sister from the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, one of the congregations who took part in Sexton's research. This image was used in Sexton's book cover. (Courtesy of Catherine Sexton)

In February this year, I had the opportunity to attend a fascinating webinar by Catherine Sexton, who was presenting research from her book, Becoming Apostolic: Conversations With Older Roman Catholic Sisters.

Unlike contemplative orders, apostolic congregations or communities are characterized by their active service and ministries — a challenge for sisters who find themselves too old to be able to carry out works that once marked their religious life.

As these sisters' social influence decreases with age, Sexton wanted to discover how they viewed or understood their apostolic vocation and if they still, in this new stage of life, considered themselves apostolic.

Her research engaged 12 Roman Catholic sisters from five apostolic-active congregations in England and Ireland, ages 70-95. The sisters were no longer engaged in ministries external to their congregation or communities, so their lives were centered in home communities.

Sexton described herself as a "practice-engaged theologian," which is the relationship among experience, practice and theological theory. The context of her research was the decline of religious institutes in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, diminishing numbers and the experience of "aging together."

They began to see that apostolic life was not just a vocation, but it was also a person becoming or 'being' apostolic for the sake of the kingdom.

She found that sisters vigorously rejected the use of the term "diminishment," and so in response Sexton reframed her research to "exploring how the understanding of apostolic life at this new stage of being house- or community-bound might limit lives and the apostolic vocation."

Her methodology was one of contemplative inquiry, theological in nature and carried out in practice as a "holy listening, a sense of encounter" — a kind of mutual lectio divina where, as the conversations evolved and a life was revealed, there was a mutual sense of God's presence. In this mutuality, she and the interviewee were "becoming interiorly freer to linger more deeply" with one another.

This lingering at certain points became a work of contemplation of respect and reverence for that life shaped by living the life of Christ and becoming "vehicles of grace for others." As the questions were pursued, the conversations led the sisters to see more deeply the meaning of their apostolic life lived in a new way.

Dr. Catherine Sexton, a self-described "practice-engaged theologian" and the author of Becoming Apostolic: Conversations with Older Roman Catholic Sisters (Courtesy of Catherine Sexton)

The questions Sexton brought to the conversations included the following: How does the enforced form of living your apostolic vocation within your community affect your understanding of the "apostolic impulse" essential to your vocation? How can this apostolic impulse still be lived in this stage of your life and its new context? What contribution can this make to your changing self-understanding of apostolic religious life and the theology underpinning it?

Through her research, these holy conversations revealed an evolution of how sisters were seeing their apostolic life.

- They were changing their understanding of what constitutes an apostolic vocation as it evolved. They began to see that apostolic life was not just a vocation, but it was also a person becoming or "being" apostolic for the sake of the kingdom. So, apostolic ministry was not only a specific employment, task or role: It evolved into an apostolic identity.

- This "identity" enabled them to still see themselves as apostolic even when their locus changed.

- Even though the women value the contemplative aspects of their vocations, some expressed an inner conflict about the increasing dependency and diminishment they experience as they age. Where some struggle, others understand and accept change as part of the dynamic of the paschal mystery. Some revealed how they were bothered by the negative social constructs regarding old age, especially for women, and the current conversations about diminishment of religious life.

- Sisters "being with and for" others was understood by most of the women in terms of total self-gift through a strong orientation to the needs of others. They recognized that all they received from God is "gift," and so in turn they can offer their gifts of time and availability, through acts of sharing, welcoming and hospitality, accompanying, listening and paying attention to and helping others. And these actions can lead to "communion" with others.

Two other questions were posed: Who am I at a later stage in life when I can no longer "do," and what do I call myself?

Advertisement

Emerging ministries noted by these sisters no longer "doing" public work were those of prayer and continuing engagement with the wider world and its needs by writing letters and signing petitions. Others included the ministry of presence, caring for each other and caring for their caretakers.

As one sister noted, "Simply by being, we can be 'mission,' an incarnation. I am a mission on earth."

Simone Weil, a French philosopher, activist and mystic, said the same thing in a different way, that merely listening is a gift from God and a fruit of prayer. She believed that the gift of complete attention given freely to another person is the greatest gift one human can give another; it can heal and restore life. Transforming attention can only be learned in prayer because that is when one most imitates God.

Becoming Apostolic: Conversations with Older Roman Catholic Sisters, published by Brill (Courtesy of Catherine Sexton)

The new reality for the sisters was described as accepting "being on the borderland," of facing loss of independence and death. But even in this new space, the sisters expressed hope that they would still be mindful of others' needs. Simple things they described as the ministry of graciousness and caring about those who care for them, being patient. It may not be possible to be outwardly concerned for the caretakers, but just making their caring easier is remaining faithful to the apostolic impulse that called them to religious life.

There was also discussion about a new call to obedience. Obedience may have once been more active and dialogical, but now the call was becoming more unitive in nature. It is a call to deeper relationship with God, and of course a gradual relinquishment of life, but not solely. Both inner and outer life is still experienced as relational. Discernment is still practiced and therefore formative of one's apostolic life to the end.

The book has much more in it about Sexton's research methods and quotes from sisters, but these were parts that stood out for me as important. As I listened to Sexton's presentation, I was thinking what a valuable gift this research is for us.

Her lectio divina conversations with the sisters could be a model among sisters themselves in community. It could lead us to reflect more deeply on our apostolic lives, not just what we did, accomplished, but who we became as apostolic in our very beings.